The Price of Security

May 15, 2018

When senior Wiley Jones arrives at school every day he expects his learning environment to be safe and conducive to his success — even if it means an unidentified administrator or volunteer might be carrying a firearm.

Jones isn’t alone in that assesment. Following the shooting in February that left 17 dead at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, the Florida Legislature and Gov. Rick Scott mandated that all Florida schools must have either an armed School Resource Officer or an armed volunteer on campus and every student have access to a mental health counselor. But that decision comes at a substantial price.

Currently only 36 of 82 BPS schools have an SRO on campus due to the cost and manpower available from local law enforcements. SRO funding derives from a combination of school district and law enforcement dollars and the state’s new mandate will pay only the school-district contributions.

“One of my campaign promises was to try to get an SRO to every school and so that was my first budget request once I got on the board,” school board member Tina Descovich said. “The problem is none of our cities or county can come up with enough money on their budgets now to meet the other half of that [money requirement] nor do we want to dig into our budget so that’s we’re running a shortfall there.”

The school board has contracted with the Brevard County Sheriff’s Department to oversee security measures and immediately following the legislative mandate, Sheriff Wayne Ivey put together the Sheriff Trained Onsight Marshal Program — nicknamed S.T.O.M.P — which calls for the arming of either school administrators or volunteers who would receive specific training from the sheriff’s department on how to deal with active shooters and also personalized medical training on how to perform CPR and apply trauma treatment.

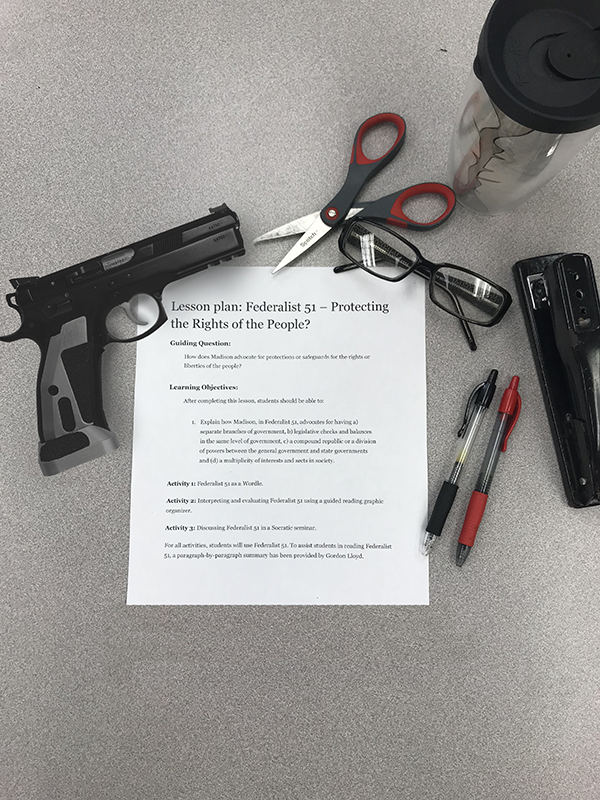

One important piece of the state legislation that led directly to the creation S.T.O.M.P is the inclusion of the Guardian Program which allows school districts to choose to arm and train volunteers in order to defend school campuses. Teachers — other than those with a background in law enforcement or military experience — are prohibited by contract from carrying firearms, but administrators and other school staff would be eligible to apply for the program.

Volunteers would be subject to a minimum of 132 hours of firearm safety and proficiency training in order to be eligible and many appear willing to sign on.

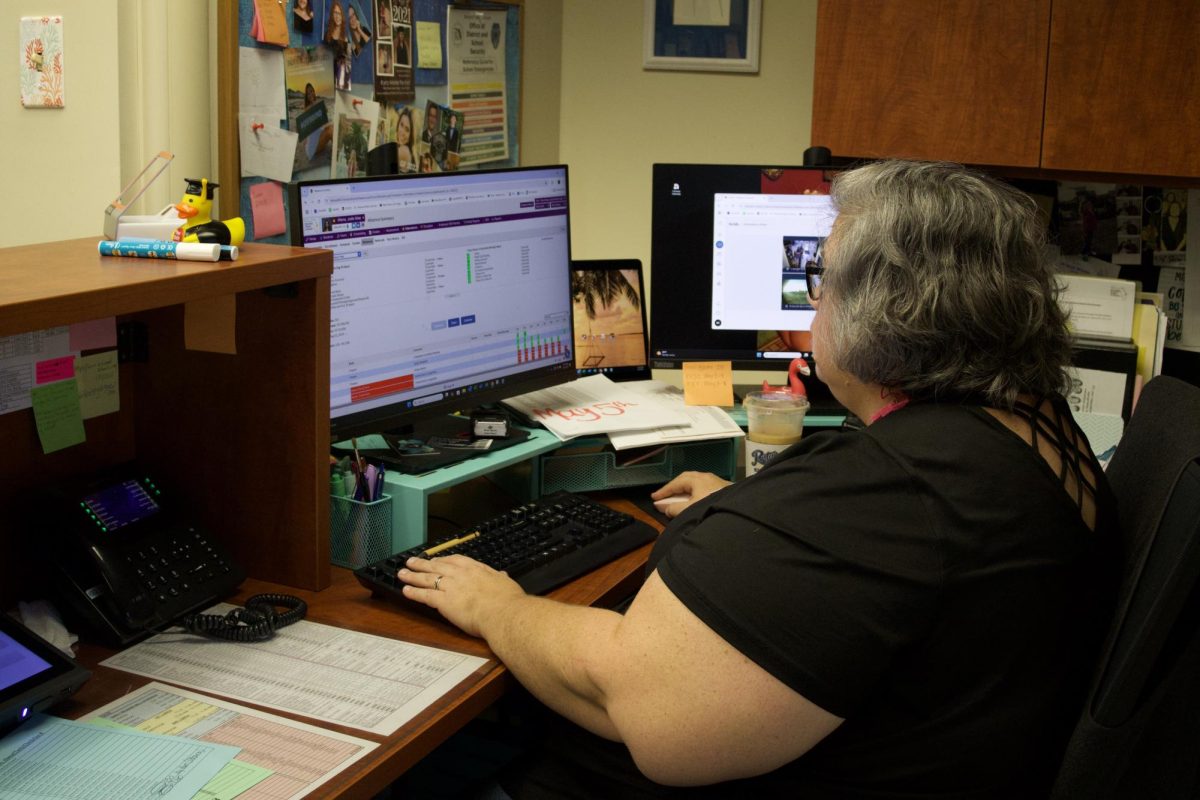

According to a survey conducted by Brevard Public Schools more than 38 percent of interviewed administrators, support staff, or other school-based professionals showed interest in serving as an armed guardian on school campuses.

The proposed S.T.O.M.P program would follow the same premise as the Guardian Program but would also require additional training for volunteers who wish to be considered. Candidates for the

program would be required to learn and receive training in first aid, CPR, trauma, diversity and mental health.

Descovich said she believes Ivey’s plan is sufficiently thorough to serve the needs of Brevard County.

“He’s upped the training intensively to 276 hours of training,” she said. “Which [Ivey] says — and I talked to other law enforcement officials — is about 20 percent more active-shooter training than any other law enforcement professional around here. So your SRO doesn’t get this intensive training and your cops on the street have not gotten this intensive training.”

Along with the 276 hours of active-shooter training, S.T.O.M.P candidates would undergo psychological screening and background checks by the district and sheriff’s office.

After studying Ivey’s plan, Jones said it made sense to him.

“If they are having personnel and not actually teachers who are well- trained and know how to respond to an active shooter, then that’s an important thing that’s really key,” Jones said. “I would feel a little more safe knowing that there’s more than one person who can protect the school from a shooting or some other incident.”

While Descovich said she believes the volunteers would be sufficiently screened and trained, a vocal segment of the community disagrees.

School board members recently held three town-hall style meetings to gauge public support and seek input and Melbourne High School student Karly Hudson, who attended West Shore for middle school, led the opposition to Ivey’s plan.

Hudson, who heads the local chapter of March for Our Lives, said the district should try to implement a solution that doesn’t require bringing in more guns onto campuses.

“I am 100 percent for the first three steps of Sheriff Ivey’s plan which calls for more mental health professionals in schools, hardening of facilities, more SROs and active-shooter training,” Hudson said. “What I am 100 percent against, is the fourth step which calls for the arming of school staff. I think there is a big risk in adding more guns on campus that aren’t held by police-grade professionals. More guns involved in an active-shooter situation will only make things worse.”

As a result of feedback from the town-hall meetings, the school board voted on May 8 to postpone implementing Ivey’s proposal to arm school staff and instead decided to hire full-time armed “security specialists” who would be required to meet the same standards Ivey proposed for qualified school staff and administrators.

According to a draft of the security specialist job description, applicants must be at least 21 years old and have at least a high-school diploma. Duties would include monitoring the interior and exterior of the school for violations of school policy, collaborating with school and district personnel and law enforcement for preliminary inquiries into violations of school board policies, communicating school policies and procedures to visitors and school personnel, investigating unusual activity on campus and monitoring students during various activities on campus and providing support in emergency situations and drills on campus.