Water fountains draw concerns from students

January 24, 2019

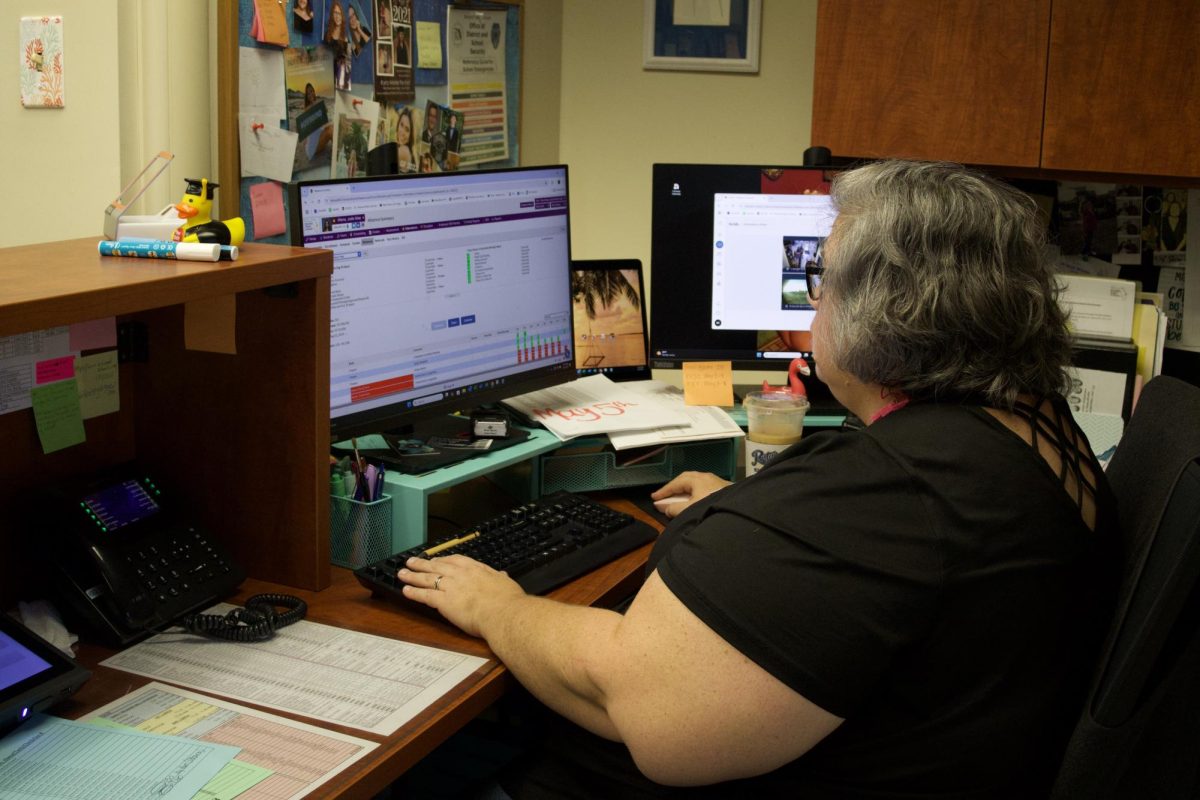

Despite various water fountains located around campus, sophomore Courtnee Reidel chooses to buy bottled water from the cafeteria like many other students every school day.

“The [water fountains] are really dirty and rusty and [water] comes out a weird tinted color,” Reidel said. “The water has a weird taste.”

The taste of the water may be caused by “metal plumbing, bacteria, treatment chemicals or organic material in the source water,” according to Waterlogic, a water cooler and dispenser company. EPA standard assessments indicate that the water is safe to drink.

“Most of the water fountains … are rusted or broken,” Reidel said.

According to the PHLP (Pennsylvania Health Law Project) Net Water ACCES Facts Final Files, “[a], majority of U.S. schools were built before 1969, and many are in need of significant infrastructure repairs for old plumbing or fixtures.”

West Shore, however, was renovated in 1998. All of the water fountains are fully functioning, yet the purchasing of bottles is more popular among the school.

“I buy waters everyday because the water fountains are warm,” junior Alexis Vander said. “I only want cold water.”

Vander buys three bottles each day, in addition to juice or chocolate milk, rather than drinking the free fountain water.

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and School Breakfast Program (SBP) programs require public schools to have free water to help maintain student health and fight obesity.

With fewer students utilizing the fountains, more plastic bottles are being bought in the cafeteria.

“It’s just water, I never felt unsafe drinking it,” senior Piper Honaker said. “It’s better for the environment than plastic bottles.”

The Earth Policy Institute claims that about 1.5 million barrels of oil create 50 billion plastic water bottle use each year in America. While West Shore has a recycling program, bottles still get thrown in the garbage at lunch. Less than one-fourth of plastic bottles are recycled.

“And these statistics don’t even account for the fuel used in transporting the water around the country and the world,” Pierre Louis, from Washington Post said.

By Emma Robinson