Controversial 1619 Project hasn’t impacted BPS curriculum — yet

November 6, 2020

When Sophomore Warrick Floyd sits down every day for AP United States History class, he is reminded of a date he’s known since elementary school, one that generations of students have learned before him – 1776, the signing of the Declaration of Independence and, to him, the founding of America. A New York Times project has a different take, however – that the true founding of America was instead in 1619, the year African slaves first grounded on American soil.

“The 1619 project is an ongoing initiative from The New York Times Magazine that began in August 2019, the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery,” according to the 1619 Project website. “It aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.”

This differs from how history is currently taught, with the Sunshine State curriculum requiring an overview be given of all perspectives from certain time periods.

“It’s a big ask, and a big difference from how we teach now,” said AP United States History teacher Athena Pietrzak. “The AP gods, or gurus, or whatever, tell me what they want me to cover, and I do my best to fit it all in the time we have. We’re taking things like slavery as a theme, and teaching them through the time period. So it’s slavery in, say, the Antebellum period and why that’s important. We’re trying to look at both sides, but we’re not particularly focused on one perspective from beginning to end.”

The 1619 Project has been surrounded by controversy since its creation, notably by historian Leslie M. Harris, who said she fact-checked it before its publishing, and her corrections were largely ignored.

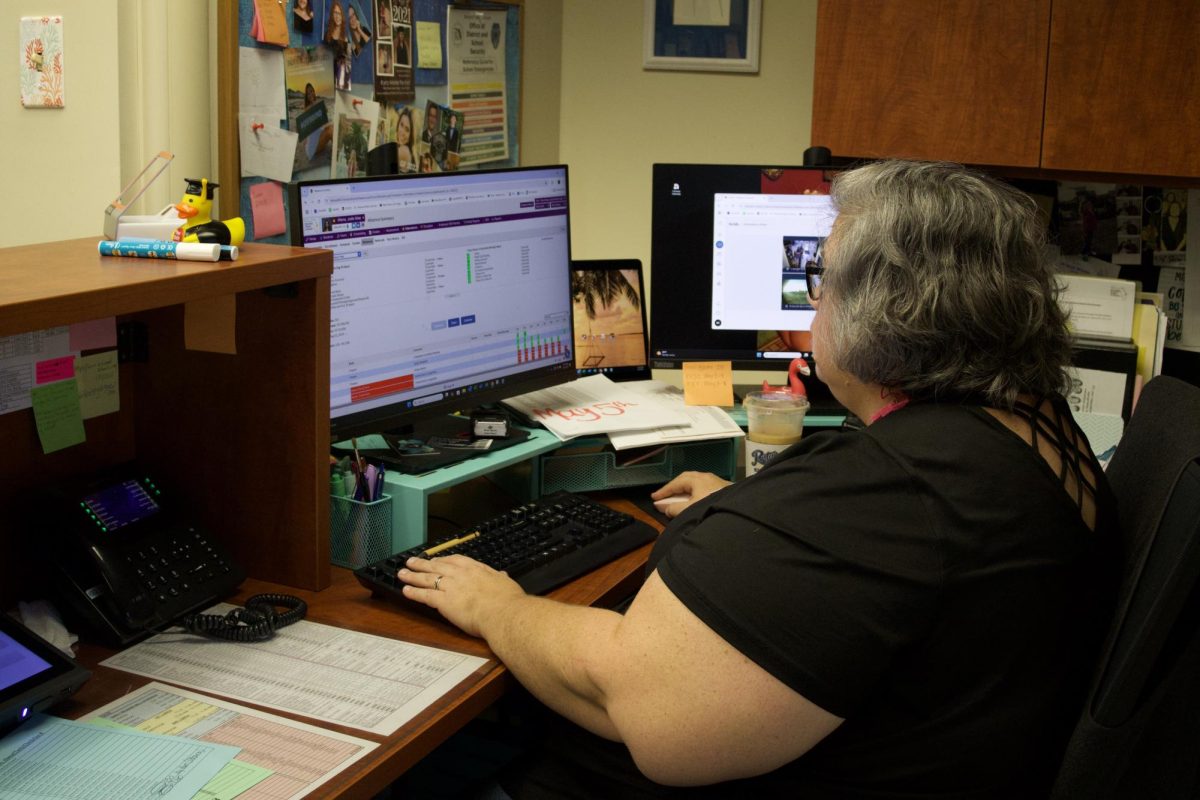

“The job of historians is to investigate and not only look for clues to our past but also to seek to understand and interpret them,” said Kimberly Garton, curriculum supervisor for social studies at Brevard Public Schools. “History is alive. For the 1619 Project, the biggest positive is that all of the written and collected works can force us to think. The Project can help us see history from a different perspective and ask more questions, grow our knowledge and develop a deeper understanding. I also think that some of the more curricular elements of the 1619 Project, if used in conjunction with other materials, could really help students think about the potential connections between current events and American History and develop a deeper connection for students to the narrative.”

Pietrzak says she tries to provide a balanced perspective on the controversial periods of American history.

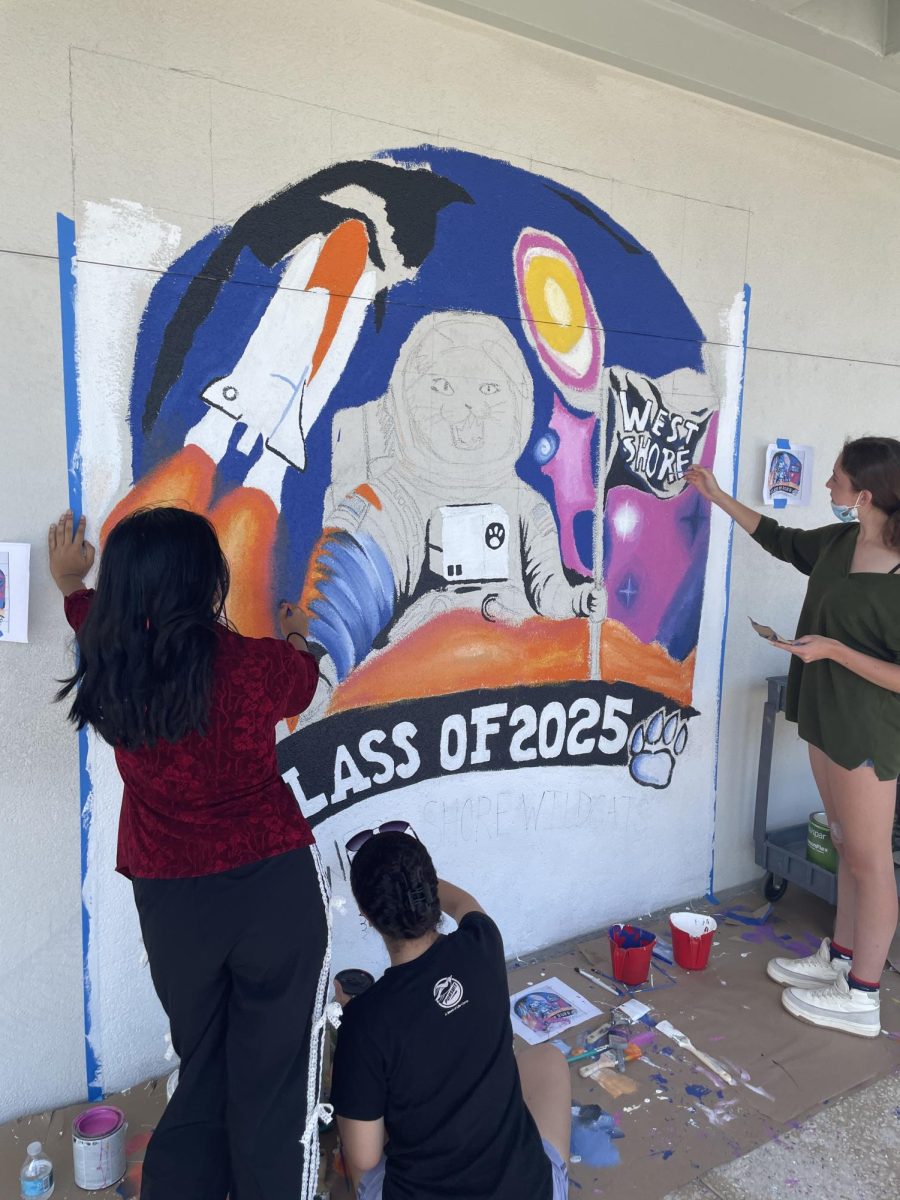

“There’s so many ways we could benefit from introducing something like those curriculums here,” she said. “I always say education is power, and I think that applies even more when it’s history. So many people don’t know how important slavery was in the founding of our nation, and I think that’s a shame. Having this sort of knowledge in your background is so important. It’s a shame we can’t provide that sort of education. At West Shore specifically, we try to give the most well-rounded view of history that we can, and sometimes I think things slip through the cracks somewhat.”

In September, President Donald Trump issued a statement promising to remove federal funding for schools that taught material from the 1619 Project, and issued his own 1776 Commission in response. This project has yet to release any material.

“Teaching about the history of America and what facts, opinions, and perspectives to include is always going to be dramatic,” Garton said. “Remembering is not an easy road to travel. The particular drama surrounding the 1619 Project and the 1776 Commission comes from the fact that these two ideas stand very far apart on a spectrum of the American story. Even historians are debating the ideas and assertions made by both. Drama also comes when the ideas behind these projects are taken up into the political quagmire.”

Sophomore Warrick Floyd says the significance of the 1619 date is being overly emphasized by the project.

“I don’t think [The 1619 Project] is accurate,” he said. “I’m definitely for recognizing African Americans, but I don’t think that 1619, the date when slaves were brought over to the Americas, signifies anything about America. I believe that 1776, when the Declaration of Independence was signed, is the founding of America. On the other hand, with the 1776 Commission, I’m not entirely sure what patriotic education is. I support nationalism, but I also understand the extremes it can go to.”

The 1619 Project also aims to teach about racism and capitalism in the modern day, and traces much of it back to slavery in America. Floyd says he sees an issue in the way this could influence students’ opinions.

“In terms of patriotic education as well, I am very against not teaching something because it is ‘not patriotic,’ as well as skewing children’s view of history in accordance with a group’s views,” Floyd said. “But I think that if a school chooses to teach that the founding of America was in 1619, and teaches nothing else, they should have funding revoked. However, if they’re teaching that 1619 was a sign that America was growing and becoming its own individual country, the president shouldn’t revoke funding. History should include a lot of things, the number one thing I am against is revisionist history. Parts of history should never be left out because it does not fit a specific agenda. Should the date 1619 never be taught? I don’t think so, it’s just another date, another time stamp in history. But I think it shouldn’t be exaggerated, and that we should teach other timestamps in history.”

Pietrzak says the 1776 Comission could set a dangerous precedent for the influence politics has on education.

“I think the issue here is that we absolutely need to be funded,” she said. “Without federal funding, teachers don’t get paid. I see a problem with current conditions in the way we teach things, but this is a borderline control of information. I think allowing the president, or government, to decide what can and can’t be taught in schools is absolutely not OK. It doesn’t matter if I agree with it or not. I think things in education are tense enough as it is, history is fighting to remain a discipline as it is. More control of information helps nothing. That’s not going to serve its purpose. I think knowing the history before you decide where you stand is an important part of being an American patriot. There’s no way to truly know where you stand unless you have all the information, and I think that is something that is sorely lacking in the way history is taught in our schools.”

According to the Pulitzer Center’s annual report, the 1619 Project is being taught in over 3,500 classrooms around the United States, but Pietrzak says it is unlikely to arrive on our campus.

“Neither of these projects are able to get any attention this year because of the pandemic,” she said. “Our history department meetings are on Zoom, there’s very little communication. Because of that, even when things like a new project get mentioned, we have no time or resources to implement that. Add to that business that it’s my first year teaching AP, and it suddenly seems impossible to even consider adding something like that. I think there’s benefit to both, really. I think we would be paying a lot more attention to both, it’s a shame our hands are tied with the 1619 Project. It’s not even a possibility because of the decision that we’d lose funding if we taught it.”

Brevard Public Schools is required to teach from the Next Generation Sunshine State Standards. From those standards, districts provide teachers with curriculum guides and recommended resources. Changing these standards is a process that can take years.

“Honestly, as the content specialist for social studies for BPS, I don’t believe either projects/curricula would, or should, change what is taught in Brevard schools,” she said. “Teachers within their classrooms then have the autonomy to use different resources and develop their curriculum. Whatever they choose, it must connect to the standard. So ultimately, a new resource or even a presidential commission would not change what social studies teachers are required to teach. That would take the state of Florida changing the standards, which takes a long time, and is always controversial, and always political. Things like this tend to happen just before and just after elections, and are generally an attempt to get more influence and control how things are taught.”

She expressed concern that changes may be difficult for teachers and students, as well.

“Right now our social studies teachers already work hard to teach their required standards with high quality curriculum and resources that show a variety of perspectives and diverse ideas, while equipping their students will the necessary skills to examine and think about topics related to social studies critically to either develop, change, or strengthen their opinions,” Garton said. “Any resources from these two projects would simply add to that endeavor.”