Textbook controversy focuses on the wrong things

Did the creators of Prentice Hall’s ninth-grade world history textbook make a mistake by creating a book that gives more attention to Islam than Judaism and Christianity? Yes, as State Representative Ritch Workman pointed out. But the mistake wasn’t in including material on Islam; it was in assuming that students would already understand the tenets of Christianity and Judaism.

It was a reasonable assumption to make. After all, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2008 76 percent of the United States’ adult population self-identified as Christian while only 0.5 percent self-identified as Muslim. So it’s not hard to see how a textbook company would believe that students didn’t need any more tutoring on Christianity in particular. In some cases, it might not even be a bad assumption: in some Florida counties, sixth-grade world history includes units on Judaism and Christianity, but not on Islam.

Still, it was a bad idea to assume that a textbook on world history didn’t need to include much information on two of the world’s major religions. It’s reasonable to be displeased by such poor coverage and take actions to correct it. It’s also reasonable to criticize potential bias, particularly in a history textbook — there are so many different ways to interpret history that special care must be given in this subject to ensure that the textbooks giving students their most reliable and canon viewpoints are as objective and factual as possible. What is not reasonable is objecting, as many seem to do, to the inclusion of Islam at all.

No matter what you believe about Islam, students in an increasingly global society need to learn about the tenets and beliefs of a religion followed by about 23 percent of the world’s population. It’s particularly vital that students understand Islam precisely because of the many conflicts and problems that occur in the predominantly Muslim region of the Middle East. How can students — and the adults they’ll become — hope to understand the conflicts in which American interests are deeply involved if they don’t comprehend the participants’ worldviews?

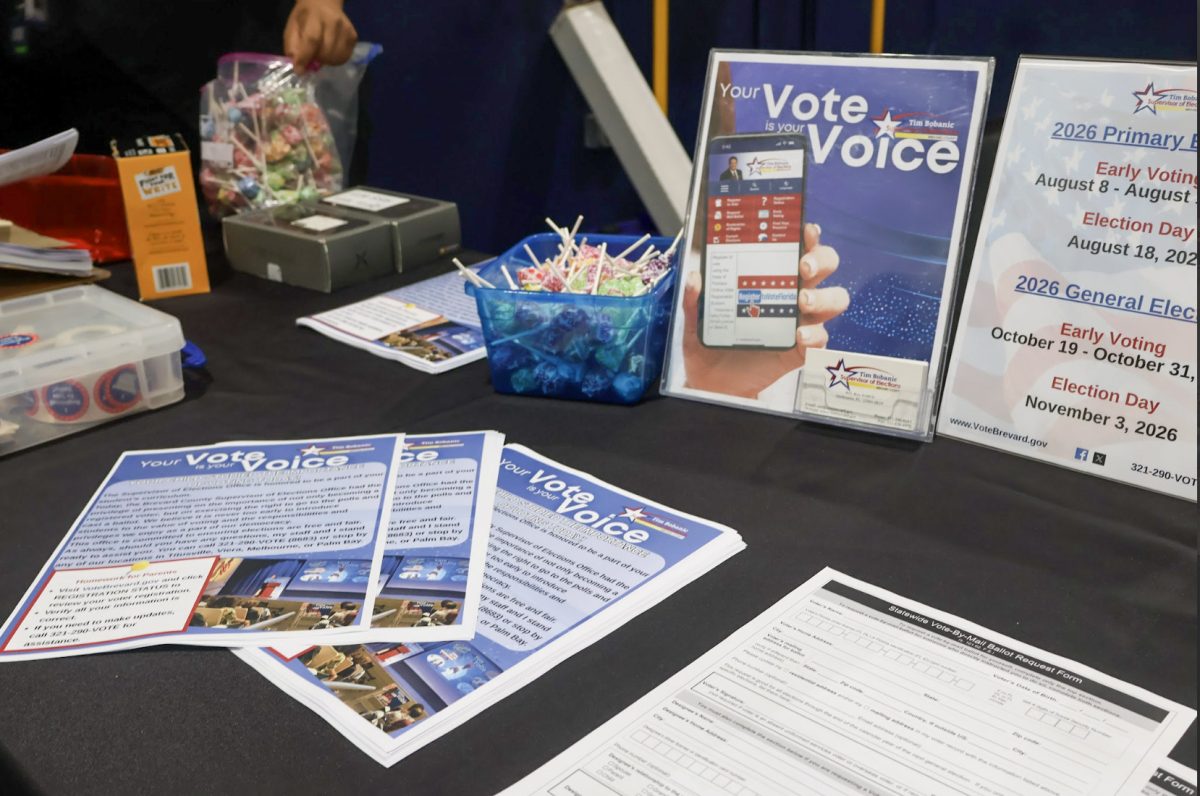

A balanced public education system should teach students about all major religions, but should take care not to present the beliefs of any as absolute truths, but as just that: beliefs. Taken in this light, the school board’s decision to print a supplement intended to balance the textbook’s coverage is a wise one. But, seen along with other elements such as the transformation of seventh-grade social studies from world cultures to civics, the furor over the textbook appears as part of a dangerous trend of refusing to teach students about parts of the real world outside America, especially those that public opinion frowns upon.

![Sophomore Isabelle Gaudry walks through the metal detector, monitored by School Resource Officer Valerie Butler, on Aug. 13. “I think [the students have] been adjusting really well," Butler said. "We've had no issues, no snafus. Everything's been running smoothly, and we've been getting kids to class on time.”](https://westshoreroar.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/IMG_9979-1200x800.jpg)