Politicians prefer cash to constituents

Former Florida House Speaker Will Weatherford.

“This is what people do when they’re desperate. That’s the kind of thing you do when you’re losing.”

That’s what former Florida House Speaker Will Weatherford told reporters after the Florida Democratic Party filed a motion on Nov. 4 to extend the polls in Broward County until 9 p.m. The motion was not granted.

The 2014 gubernatorial election was widely believed to be a toss-up, which meant that each candidate needed to be extremely competitive in order to win. In Charlie Crist’s case, he needed to capture the minority vote, as well as the votes of the less politically interested public, both of which tend to be Democrat and reside in South Florida, namely Broward County.

Given the importance of Broward to the Crist campaign, the Florida Democratic Party’s move makes sense politically and so you might be asking yourself “why is Weatherford’s quote a big deal?”

If Crist had shown himself to be politically adept, there wouldn’t be an issue. But that hasn’t been the case. Crist needed the Latino vote to win, but rather than pander to them and do whatever possible to get their vote, he did the opposite. Rather than show interest in policies that Latinos like, such as statehood for Puerto Rico, Crist took a step in the opposite direction and endorsed Puerto Rico’s anti-statehood governor. There’s tone deaf, and then there’s not being able to hear the music at all.

Because of his bad American-Idol-audition political sensibilities, it makes me think that perhaps there were serious legal and democratic concerns to be had about the voting in Broward. Redistricting in August has caused confusion, which resulted in voters showing up at the wrong polling place and poll workers being unable to tell them where they should be, as well as some voters being issued voting cards, which improperly listed their polling place. On Election Day, voting equipment experienced several mechanical failures and polling places opened late. Secretary of State Ken Detzner said that nothing in this situation was “systematic,” but it doesn’t have to be systematic to be problematic, especially when it comes to voting. It’s a fundamental right, and no voter deserves to be disenfranchised, even if it’s accidental.

So behind Weatherford’s words lies an implication I detest. One, that it’s “desperate” to do something that was, for all intents and purposes and with good reason, taken on behalf of voters who were being marginalized. Two, that this move could only be political.

What’s frustrating is that this is a safe assumption to make. We can’t trust our politicians to do things for us, but we can rely on them to do things for themselves. And it’s not necessarily their fault.

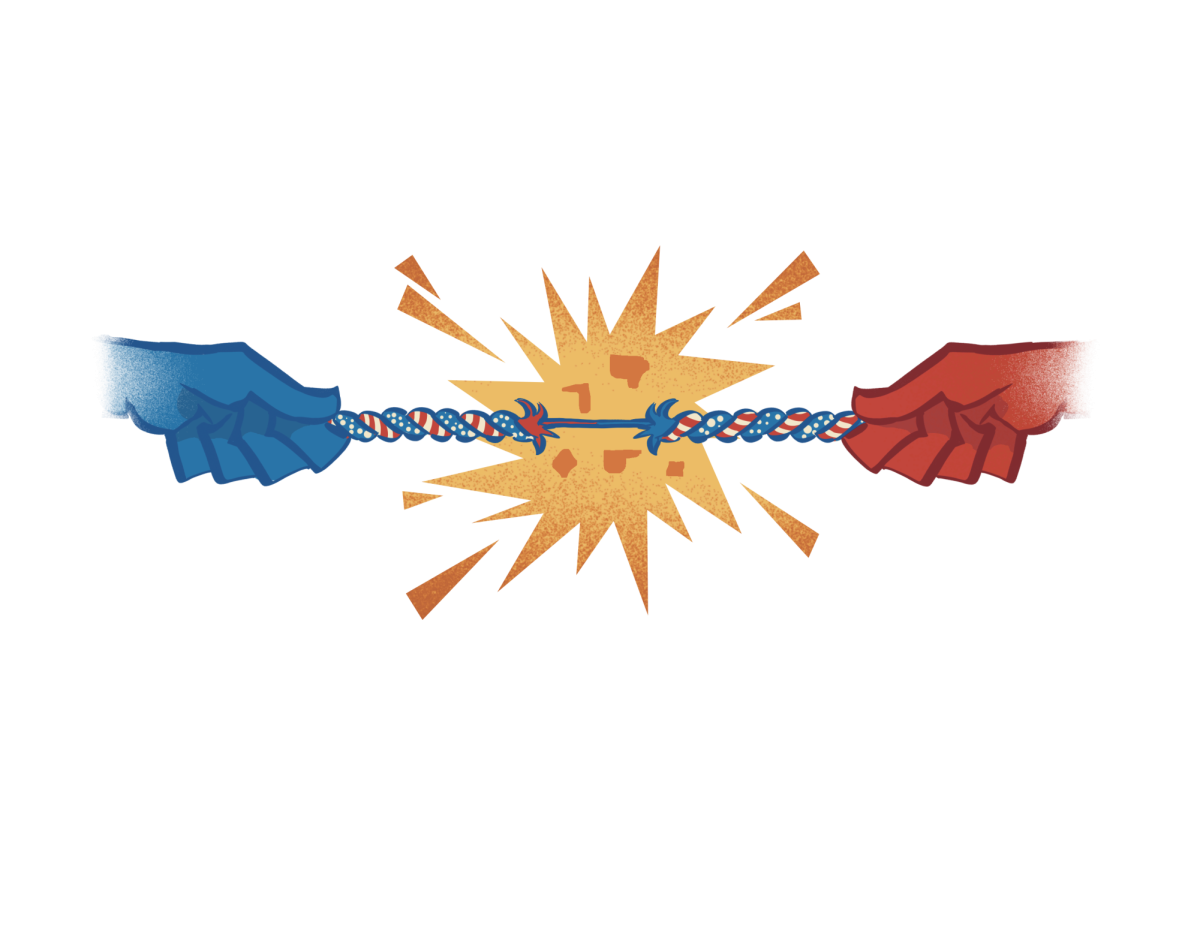

Politics is a system. It’s a network comprised of interest groups, money, the people, and of course, the politicians. And when we’re comparing our current politicians to those in the past, we need to understand that everything, from the bills signed to the articles written, is a product of a system and a time period. The Civil Rights movement or the New Deal wouldn’t happen today; the system isn’t ripe for it.

This is especially true because today’s political system is characterized by an influx of money. Since 1986, the cost of winning an election for both the House of Representatives and the Senate has steadily increased and is now in the tens of millions. Wealthy individuals and political actions committees make up most of the funding, and since the late 1980s the number of PACs has nearly tripled. More than ever, those with money are able to exert a disproportionate amount of influence.

Say you do start out with good intentions; you’re running for Congress because you truly believe in protecting the environment, or our civil liberties, or because you believe our healthcare system needs to change. So you survey the field and you make a pitch to your local representatives of whichever party you’re choosing to run for and you’re very hopeful. Suddenly, you realize that you will need millions of dollars. This might mean spending some of your own money. It might mean looking around for a wealthy donor whose interests intersect with yours. But more often than not, it means changing yourself to attract said wealthy donors and spitting out as many inflammatory sound bites as you can. And then by the time you’ve reached office, not only must you focus on being re-elected in order to accomplish your “goals,” but you realize that you aren’t the politician who chose to run in the first place. What had started out as selflessness became corrupted by a system that forces you to play by its games.

It hasn’t always been like this. Sure, politics has always been a game to a certain degree, but with money’s newfound power it has become much more prevalent. Interest groups and rich people can, with a shower of cash, influence how our politics play out. A little dab of money here, you can fund a guy to run for president. A little dab of money there, and you can completely take over a state house, as Sheldon Adelson did with South Carolina.

In this current climate of Citizens United and unlimited spending, it has no longer become about the people. It’s now about how much money you can get, how much media time, how many ads you can throw on TV and how many cities you can get to in a day. With money, politics has lost its personal spark. We’ve had presidents, Democrat and Republican, who have done things for the people. But that was in another century.

The entire system of politics has been revolutionized, and the great, but terrible, thing about systems is that they perpetuate themselves. Through the revolving door, money and corruption flow in and out as slippery as oil. And if we don’t act, the snarky soundbites about issues we need to take seriously will only keep coming.

The early 1900s saw increased awareness about corporate power, the 1960s major changes in civil rights. What will the history books say is 2010’s legacy? c