Quarantine measures — while painful — prove successful

November 24, 2020

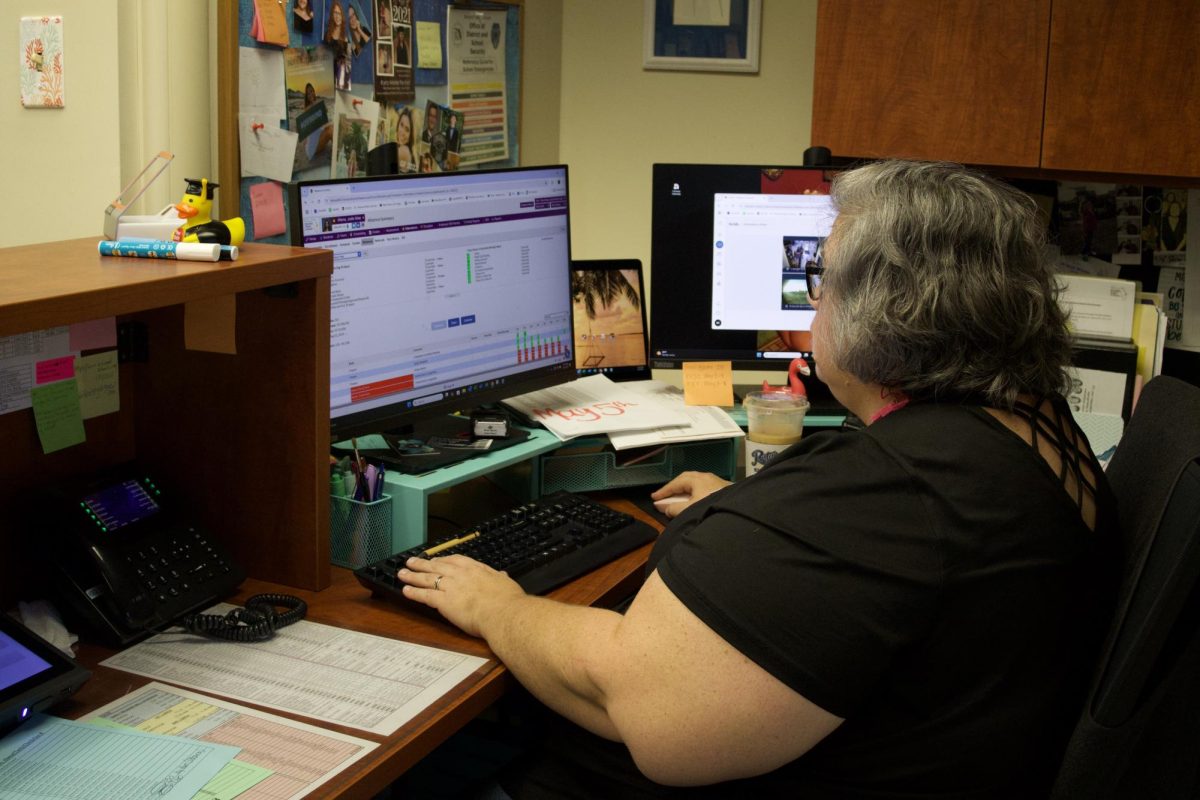

Senior Madison Ainbinder had a “weird, fuzzy headache” and a sore throat the evening of Nov. 7. Two days later, she tested positive for COVID-19, and the school’s administrative team began its contact-tracing procedure.

“I was super-disappointed and nervous, because I was around people earlier on Saturday,” Ainbinder said. “In that sense I was super-nervous that I may have been spreading [COVID-19], which wasn’t my intention. I was disappointed as well because I’d have to be out of school and away from soccer.”

When the school and Department of Health received news of Ainbinder’s positive COVID-19 case, students who were within six feet of Ainbinder, for a cumulative 15 minutes over a 24-hour period, were instructed to quarantine for 14 days.

“Once we are notified that a child was either on campus and tested positive, or they have to leave because they’re showing symptoms, we immediately go to the teachers of those students, and we immediately get their seating charts,” Principal Rick Fleming said. “Then we sit with the teacher and say, ‘OK, give us the seating chart. Is this child within six feet?’ Some teachers, with smaller classes, may have more space in between, so we don’t necessarily have to quarantine all of those kids. If there’s passing time where they’re near each other, we leave that determination up to the teacher to notify us of the six feet for 15 minutes or more.”

Staff members are required to alert the administrative team of COVID-19 symptoms or a positive test; but, according to Fleming, there is no method to enforce parents and students to do the same.

“We have put out messages that should you or your child develop symptoms in your household, please let the school know,” Fleming said. “We ask to be notified by parents, but sometimes they aren’t always honest with us. We’ve had parents want their kids to school with symptoms, but not necessarily a positive test. Any symptom other than an earache or a toothache or a sharp stick in the eye, are COVID-19 symptoms, unfortunately.”

Student are sent home to quarantine if they came into direct contact with a positive COVID-19 case. Students who are “a contact to a contact” are not ordered to quarantine. This procedure often leads to confusion, according to Fleming, especially for students who are sent home to quarantine, while their siblings are allowed to remain on campus.

“Many of the parents have been understanding,” Fleming said. “They’re not necessarily happy, but they understand we’re doing everything we can to keep students safe. The biggest issue we’ve had is parents being upset because their child is quarantined, and is not just going to miss school, but extracurricular activities.”

Ainbinder’s mom, Karen Ainbinder said her daughter’s quarantine “drastically affected [her] day-to-day life,” as her entire family quarantined within her household.

“I wasn’t surprised [Madison tested positive] based on the number of COVID cases lately,” Ainbinder said. “I was disappointed that she was going to miss [soccer] Senior Night, but was relieved that she had very mild symptoms.”

Ainbinder said her family has continued to take precautions, such as wearing masks and avoiding large gatherings.

“I believe the school is doing everything they possibly can to prevent the spread of the virus,” Ainbinder said. “Having to be quarantined is not ideal, but it is necessary.”

In the past, students who were sent home to be quarantined tried to use proof of a negative COVID-19 test, in order to return to campus before the end of the 14-day quarantine period. But Fleming said the school will continue to follow the rules set forth by the Department of Health and the School Board.

“The incubation period of the virus and showing symptoms is three to eleven days,” Fleming said. “We’ve had students we’ve sent home, that haven’t shown symptoms for seven days, and on the eighth day, all of a sudden they start running a fever. The difficulty for the parents is understanding that incubation period, and that [students] can’t come back to school with a negative test.”

Once administrators collect seating charts from teachers, they can determine which students need to be sent home to quarantine. Those students are called into the cafeteria, which Fleming has termed the COVID Tank.

“Usually the teachers can deduce [which student tested positive],” Fleming said. “We want teachers to be aware, that way we can contact trace around where that student is sitting. The students end up knowing too, because we’re a small school.”

Students in the COVID Tank are told they have been in direct contact with someone who tested positive for COVID-19. Fleming typically waits with the students while Assistant Principal Catherine Halbuer calls the students’ parents to notify them of the situation. After a parent is notified, their student is dismissed to go home and quarantine.

“It’s frustrating for me,” Fleming said. “Because as the principal of this school, my main focus is on curriculum, college decisions, meeting with guidance counselors, calling college admissions people — I can’t do any of that because I’m tied up doing contact tracing. We’re calling parents and sending students home to quarantine, and I’m up in the cafeteria while Ms. Halbuer is calling parents. We got it pretty much down to a science. It’s frustrating nonetheless, because all of us are dealing with things we never thought we’d have to deal with. But if students aren’t safe, and the school isn’t safe, then all of those other things that we do here, can’t be done.”

Contact tracing also carries into extracurricular activities. When students test positive for COVID-19, they are asked to give the school names of students who they come into contact with through lunch, sports or other scenarios outside of the classroom.

“I think it definitely does help if there are people that I was around that are getting quarantined,” Ainbinder said. “I think the school’s doing the best that it can. I think that’s been shown in our case numbers, because they’re definitely lower than other schools. So I think our administration has done a really good job.”

Fleming said the contact tracing process can be “iffy,” as administrators have to rely on information from students, and sometimes coaches, to quarantine students correctly.

“There are some kids who I was barely around who got quarantined for two weeks because they sit in a relative vicinity to me,” Ainbinder said. “And now they’re out of all of their activities. So in that sense, sometimes there could be better ways. I know some people that I was around more so, that aren’t quarantining because they were [e-learners] or I eat lunch with them. There are some limitations, but [the] administration is doing the best it can.”

Despite any reservations students and parents may have toward an unexpected quarantine, Fleming said the results thus far have proven effective.

“At least four [students] ended up testing positive during their quarantine period,” Fleming said. “I think the proof is in the pudding. If those four students stayed on campus and started showing symptoms, they could have infected multiple people. Which means we would have had a cluster. And I don’t want to be like Eau Gallie [High School] and shut down our school. We’re going to be very prudent with our quarantine because I want to stay open. Quarantine — as painful as it is — does work.”