No one like me

Limited diversity spurs conversation on campus

Every year, on the first day of school, senior Isaac Pierre is faced with the same fact: He is the only Black person in at least one of his classes.

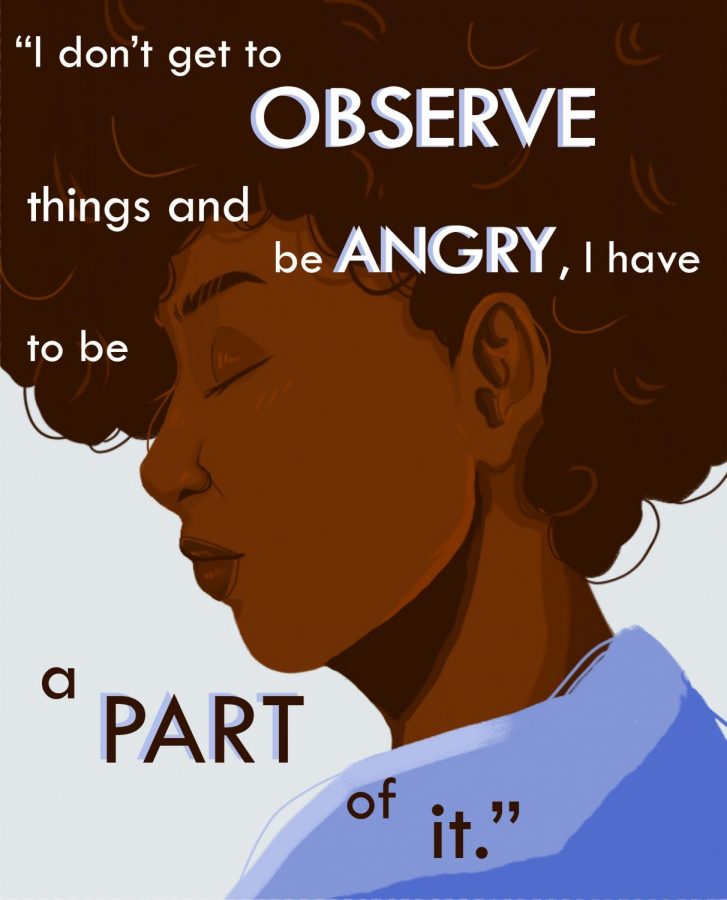

“I have definitely noticed being treated differently as a result of my race,” Pierre said. “It forces me to cope firsthand with any racial tensions on campus. I don’t get to observe things and be angry. I have to be a part of it. I think it’s especially bad because race-driven incidents occur to the point where it becomes normal.”

In Brevard County, 9.7 percent of the population is Black. In Melbourne, that number jumps to 10.39 percent. At West Shore, that percentage is 2.7, which is a slight decrease from past school years, such as 2016-2017, when the population of Black students was 3.5 percent.

Natalie Brown, a 2014 alumna and Cornell graduate, said she “was most definitely impacted by [her] race while attending West Shore.”

“I just didn’t have the vocabulary to describe [the impact] yet,” Brown said. “A lot of friends would make ‘Black jokes’ that I would laugh along with at my own expense. I didn’t acknowledge how uncomfortable these micro-aggressions were so as to not rock the boat.”

Principal Rick Fleming said such incidents do not go unnoticed.

“We try to be as aware as we can when students are being racially discriminated against,” Fleming said. “It’s our No.1 priority to make sure our kids feel safe and comfortable on campus. And part of that is trying to get more people of color on campus. I’ve been reaching out to schools with a larger African American population to encourage students to apply. There are many African Americans that we would love to have here that I worry just don’t feel welcome given the way things are, and I’m doing my best to change that.”

Fleming said the lack of diversity is not due to a lack of merit within diverse communities.

“One of the issues we’re facing is how many students struggle with the infrastructure required to come here,” Fleming said. “George Floyd’s death, along with other events, really highlighted a lot of systemic injustice in our country. I think many areas in Brevard [County] with a higher African American population are areas we see the least represented here. Many students carpool, as well, so I think it’s easy for some of these kids to feel stuck and like they have no chance of coming here.”

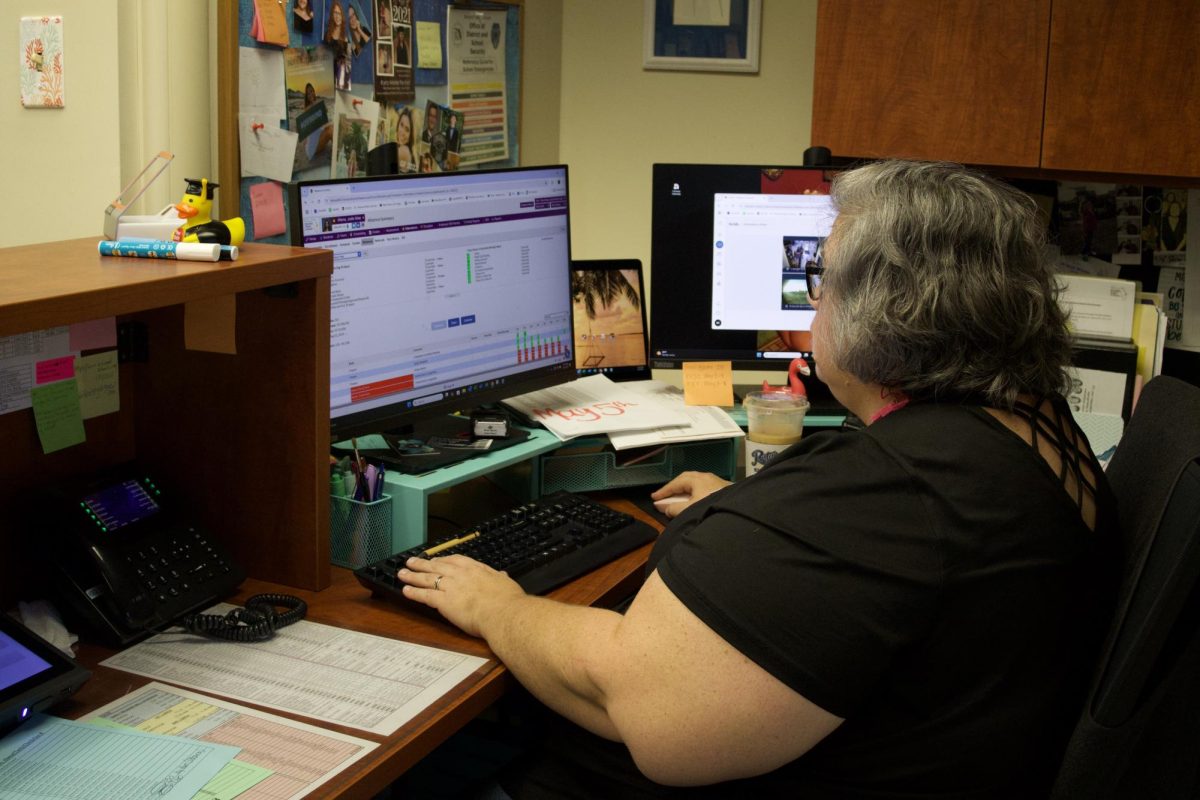

People of color also are underrepresented in faculty and staff — with the only nonwhite staff on campus being janitors, cafeteria employees and Spanish teachers. The only Black teacher in the school’s history, Kimberly Harrell, was a math teacher who transferred from Satellite for West Shore’s grand opening in 1998.

“I didn’t consider how the only people of color in almost every academic space I’ve ever been in were janitors or culinary staff until college,” Brown said. “But for those more aware at that age than I, I think this really limits students from visualizing themselves in many roles. I had never had a non-white teacher until college, and I think it would have been incredibly influential to have a Black teacher who could understand my experience, relate to me and share their experience in order to flourish in predominantly White spaces.”

Junior Logan Jenkins said he does not believe the issue to be as dire.

“I’m White, and I keep up with political topics because they interest me, and I would love to have a career in politics in the future,” Jenkins said. “I have noticed the lack of diversity on campus, I haven’t really thought about it too much though. Race isn’t really something I think about when talking to people, which is mostly why I’m not hyper-aware of it, but I guess it’s something I’ve noticed. To be honest, I think [the lack of diversity] has a lot to do with a general lower population of minority students in the area surrounding West Shore, especially north of the school. It could also be an income or education gap in races in our community as well.”

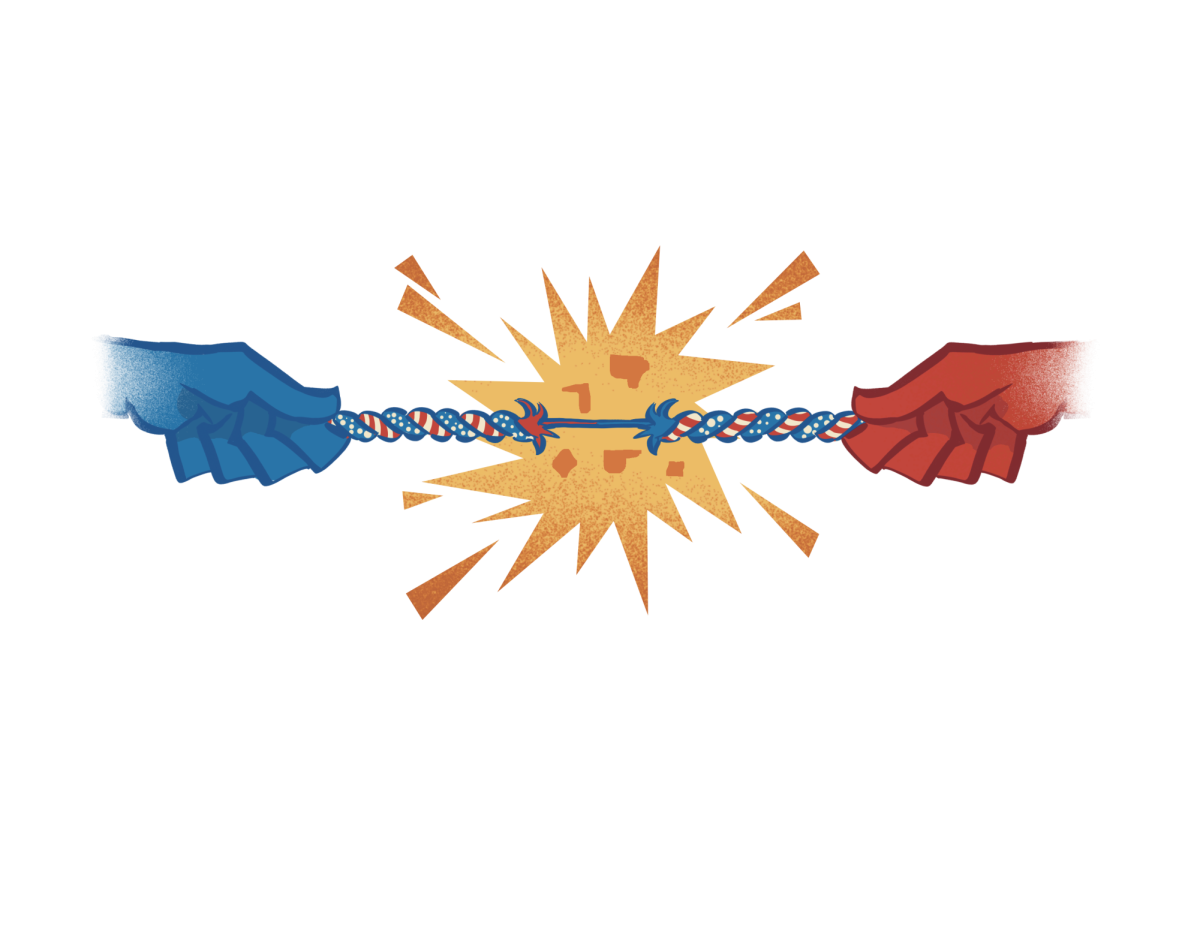

In September, President Donald Trump signed an executive order restricting government agencies, educational institutions and nonprofits from practicing diversity training, calling it “un-American.” Since then, the NAACP, National Urban League and the National Fair Housing Alliance have filed lawsuits claiming the order to be unconstitutional.

“I actually attended diversity training over the summer with the rest of the principals in the district,” Fleming said. “The idea was that every principal would be trained, and then would pass the information onto their faculty and staff. Unfortunately, due to COVID-19 and the limited communication, we didn’t have time to make that happen. I plan on making sure it does, though.”

Diversity training has a controversial history in America, with ongoing debates over whether or not it is helpful or even harmful.

“Diversity training, while seemingly well-intended, essentially teaches faculty members to treat students differently if they have a different color of skin,” Jenkins said. “Is that not inherently racist? It doesn’t matter whether the beneficiaries are White, Black, or brown; racism — that is, the discrimination of people based on the immutable characteristic of their race — is racism, regardless of who benefits. Diversity quotas, sex quotas, religious quotas, quotas of any kind that discriminate against or in favor of certain individuals are wrong not only morally, but wrong for the school system as a whole.”

Despite this, Pierre said he believes increasing diversity to be beneficial.

“It would be nice to see more people that look like us represented on staff,” Pierre said. “Some students of color may aspire to be teachers and that inspiration would be beneficial to them. I think it’s important to mention that racial issues don’t only exist at West Shore, people of color have been going through this for years. As teens, we are still developing, but that doesn’t justify immaturity. A trend I’ve noticed is that racial targeting increasingly gets worse as we get older. At first it begins as small jokes and turns into blatant remarks that are offensive.”

Brown said she faced stereotyping as she looked toward life after high school. She said parents of her peers assumed she was only considering historic black universities or community colleges.” Instead, she graduated from Cornell University in 2018 and became a data and policy analyst at Acumen in Washington D.C.

“When I went down a very different path and was accepted to an Ivy League university, my peers would say that I only got in due to affirmative action,” Brown said. “As we move forward with an awareness of racial conflicts, I wonder about administrations. Will they prioritize student safety to ensure that all students can be safe? Or address hate crimes against minority students swiftly? Or will they turn a blind eye? I don’t know, but I hope it’s the former over the latter for my fellow Black students’ sake.”

Hi, my name is McKenna Slaughter. This is my third year on staff and I am this year's editor in chief. I am thrilled to be a part of this staff while working...

This is my first year on The Roar staff and I'm super excited to draw for the newspaper on the design team!