Amid hundreds of recent executive orders, President Donald Trump quietly signed Executive Order 14224, “Designating English as the Official Language of The United States,” on March 1 to create a “unified and cohesive society … [with] one shared language.”

“We all understand that English is the main language here,” President of the East Asian Chapter of Multicultural Club and sophomore Maggie Qin said. “In some states, especially in the south, there may be a lot of Spanish speakers, so the executive order is showing that the United States doesn’t focus as much about different cultures and diversity … but it could boost our national identity and give America priority, which is a good thing.”

A lesser-known effect of the executive order is the rescission of Executive Order 13166, “Improving Access to Services for Persons With Limited English Proficiency (LEP),” which gives agency heads the power to make decisions on LEP programs — such as the ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) programs at schools — instead of having one set of federal guidelines.

Moving from Colombia to the United States at 11 years old, World Languages Department Chair Alexandra Stewart said she sees value in language programs as her siblings relied on an ESOL program in order to earn a proper education.

“Imagine coming into a country where you don’t know the words and don’t know what’s happening,” Stewart said. “They dump you in a school and you have to just figure it out … Without [ESOL programs] the progression of understanding the language would be so much slower.”

Stewart said she worries for non-English speaking students in states with worse education systems than Florida’s, such as New Mexico, which was ranked the worst state for education according to a Wallethub study.

“The level of proficiency across the board is going to be affected and likely not in a positive light,” Stewart said. “Because Florida has around 11 million immigrants, we are really good at what we do [for ESOL and other LEP programs] and all of our counties have a plan to deal with [English Language Learners] … But not every state is so well put together, and leaving it up to the whims of that state’s political leanings might mean that it is an unequal setup in different places across the country.”

Having been the sole member of an ESOL program in a predominantly white Missouri town, junior Annie Nguyen said the program, which was under the former guidelines set by the newly rescinded executive order (13166), was not set up well.

“They only taught me how to write my name and how to write common phrases, and they tried teaching me how to say them, but I couldn’t ‘get it’ quick enough for their liking,” Nguyen said. “So they just skipped over teaching me [proper] pronunciation. Eventually, when they thought that I could understand basic directions and would respond to their hand gestures, that’s when the program stopped.”

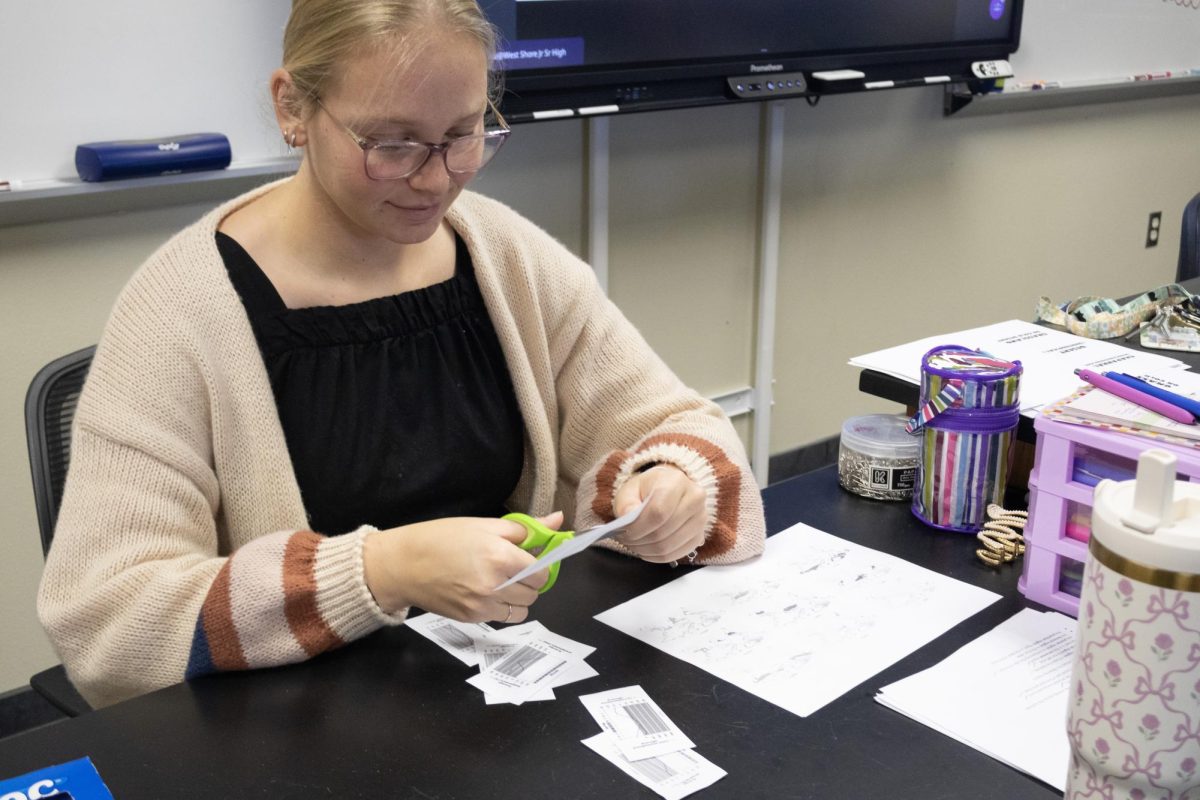

On the other hand, Qin, who moved to the US when she was 11 years old from Shijiazhuang, China, said she had a generally positive experience with the ESOL program at Odyssey Charter, a K-12 school in Brevard County.

“In ESOL, I would take a test at the beginning, middle and end of the school year and was assigned a teacher,” Qin said. “She would stand next to me for several classes, definitely English class and sometimes social studies, and she would check if I understood the content. I also had extra time for tests when I was in the program. In the middle of my sixth grade year, after a year and a half of being in ESOL, I took a test and was told I’m out of the program. I was definitely ready to go on my own. I could already communicate with people and had all A’s, so that was all adequate.”

Since the structure of ESOL programs may change given recent legislation, Qin said guidelines should consider the social impact on students learning English.

“It’s useful to have the teacher see the student during classes, but if a student is trying to integrate into the class, it doesn’t really help them to do so,” Qin said. “The teacher should help with the student’s assignments after lessons, not during. I felt more isolated from other people because they would think, ‘Oh, why does she have a teacher standing next to her?’ It just wasn’t easy [to socialize].”

Qin wasn’t alone. Speaking only Vietnamese until elementary school, Nguyen said she faced similar social difficulties in school due to her language barrier.

“I don’t think it was obvious that people looked down on me because of my language barrier at first, but I didn’t master the language for a while and only lost my accent in second or third grade,” Nguyen said. “It wasn’t until then when things started to be normal for me socially, but no one could understand me for a long time, which prompted them to give up when trying to communicate with me. It stunted my social growth, and I didn’t know how to make friends as a result of that.”

For students like Nguyen, the need for English expanded beyond the classroom and into the real world.

“I’d get home from school and have to teach [my mom] what I learned,” Nguyen said. “I had to help her translate the bills even though I didn’t understand any of it. I had to speak for her at the bank and order for her at restaurants because even when she got comfortable speaking English for simple tasks, I knew that facing people who judged her for her accent affected her, even if she tried not to show it.”

Nguyen’s mother lacked exposure to English since she worked as a restaurant busser once she came to America in early adulthood, which didn’t require much communication.

“Having programs centered around helping [immigrants and non-English native speakers] learn a language and navigate an entirely new country with an unfamiliar culture and unfamiliar language is very helpful,” Nguyen said. “An [English learning] program would have definitely helped [my mom].”

Additionally, Nguyen said students in predominantly Spanish-speaking schools, for instance, could face employment issues similar to those her mother faced.

“Without the English immersion from attending a predominantly [English-speaking] school, students wouldn’t be provided opportunities to be successful in the workforce as their English isn’t as strong,” Nguyen said.

By scaling back on ESOL and LEP programs, the disparities between native English speakers and English learners would grow rather than help create a unified culture under a single language, Stewart noted.

“It would be my fear that we would now have an even unequal implementation of requirements for students to gain mastery of a language in the country they’re going to be living in, which is so important for future job prospects, a future in higher education and in being good citizens of this country,” Stewart said.

Stewart said non-native English speaking students “might have a challenging time when they get to difficult material” if they are either not placed into an ESOL program or taught poorly in their program.

“The state of Florida has pretty robust rules now, but if they choose to change the rules since it is expensive to run these programs,” Stewart said. “It could impact the ratio of teachers to students. Instead of needing 50 students in an area or school to get a teacher, this could change to 100 students. It might not be a bad thing, but it could mean the screening process may be less rigorous and we could miss students who need ESOL services.”

Having researched ideal settings for learning new languages, Stewart said that by building up a student’s skills in their native language, students will also strengthen their non-native language skills.

“As somebody certified in English and Spanish, I have seen English scores double when teaching native Spanish speakers Spanish in the classroom,” Stewart said. “Maybe that portion of language learning education will be cut back [due to the legislative changes], and that would be a shame because nothing is better at helping students learn English than improving their knowledge of the structure of languages from multiple perspectives.”

While she hopes that the rescission of former guidelines will provide a clean slate meant to improve ESOL and other LEP programs, Nguyen said she worries that the cuts reflect a shift in America’s national identity away from supporting its diversity.

“America has always prided itself on being a melting pot of different cultures, it’s what the American Dream is all about,” Nguyen said. “Even though [decentralizing ESOL programs] seems insignificant, on the large scale, this could be very harmful. It could be taking steps to further ostracize the marginalized communities that make up the backbone of America. But I hope as long as you have the drive, anyone can make themselves better and start a new life in America, because that is the version of the U.S. it sells to other nations.”

![Sophomore Isabelle Gaudry walks through the metal detector, monitored by School Resource Officer Valerie Butler, on Aug. 13. “I think [the students have] been adjusting really well," Butler said. "We've had no issues, no snafus. Everything's been running smoothly, and we've been getting kids to class on time.”](https://westshoreroar.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/IMG_9979-1200x800.jpg)