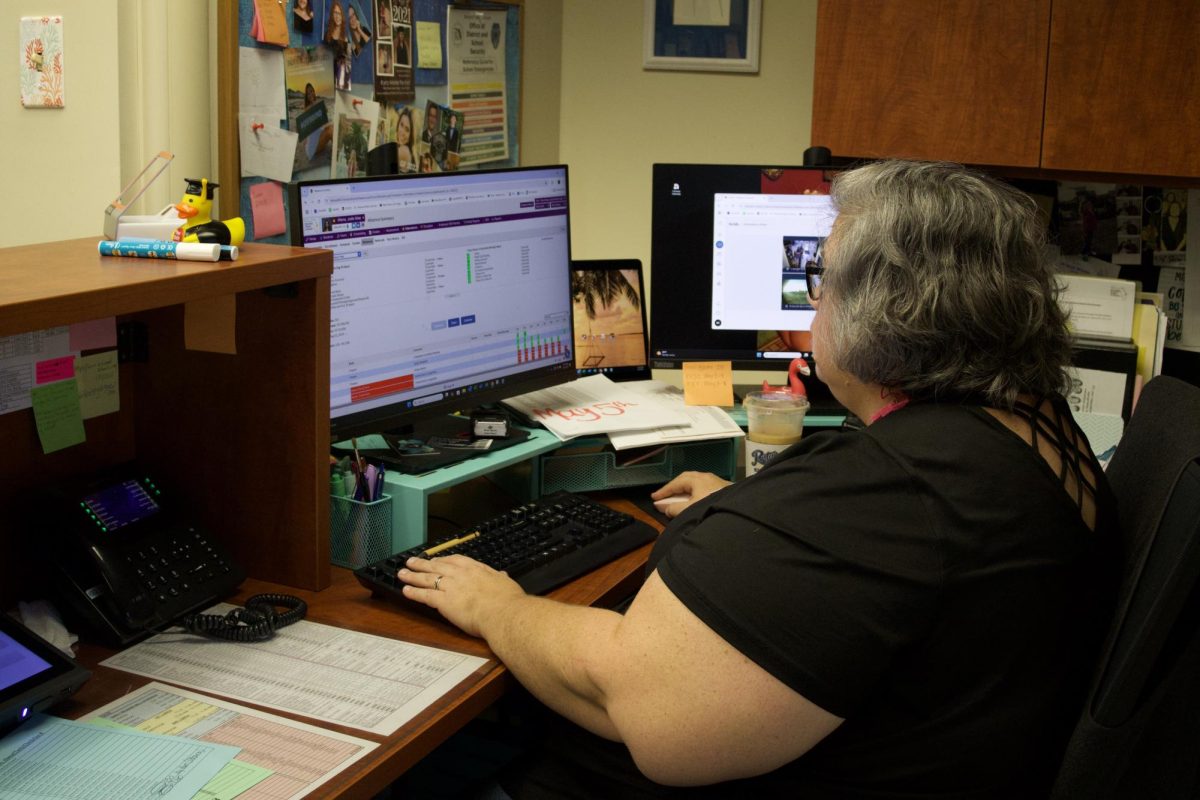

INEQUITABLE EVALUATION – ADHD often goes under-diagnosed among girls

Junior Hadley Balser was diagnosed with ADHD at age 6 after her first-grade teacher noticed she was inattentive in class. Oftentimes it is not until girls are in their mid-to-late teenage years — sometimes even their 20s — that they realize they might be neurodivergent.

“When I was younger, I hid my ADHD from most of my friends because I thought that I would be judged or deemed as ‘special needs’ at school,” Balser said. “Of course, growing up has led me to realize that there’s nothing wrong with having ADHD or needing special needs programs for school. Everyone needs a certain amount of support in order to succeed, and everyone’s different. As long as the idea that every student is different and requires different things is encouraged, I feel that ADHD will become less stigmatized.”

Tracy Otsuka, an attorney who runs a podcast titled “ADHD for Smart-A** Women,” has become a leading advocate for girls who might be neurodivergent.

“The girls who figure out that what’s going on with their brains — [that] they just have this different brain with ADHD — are not filled with shame about it,” Otsuka said. “We need to get out there and talk about it. I think the more we can talk about its strengths while also understanding its weaknesses, the better.”

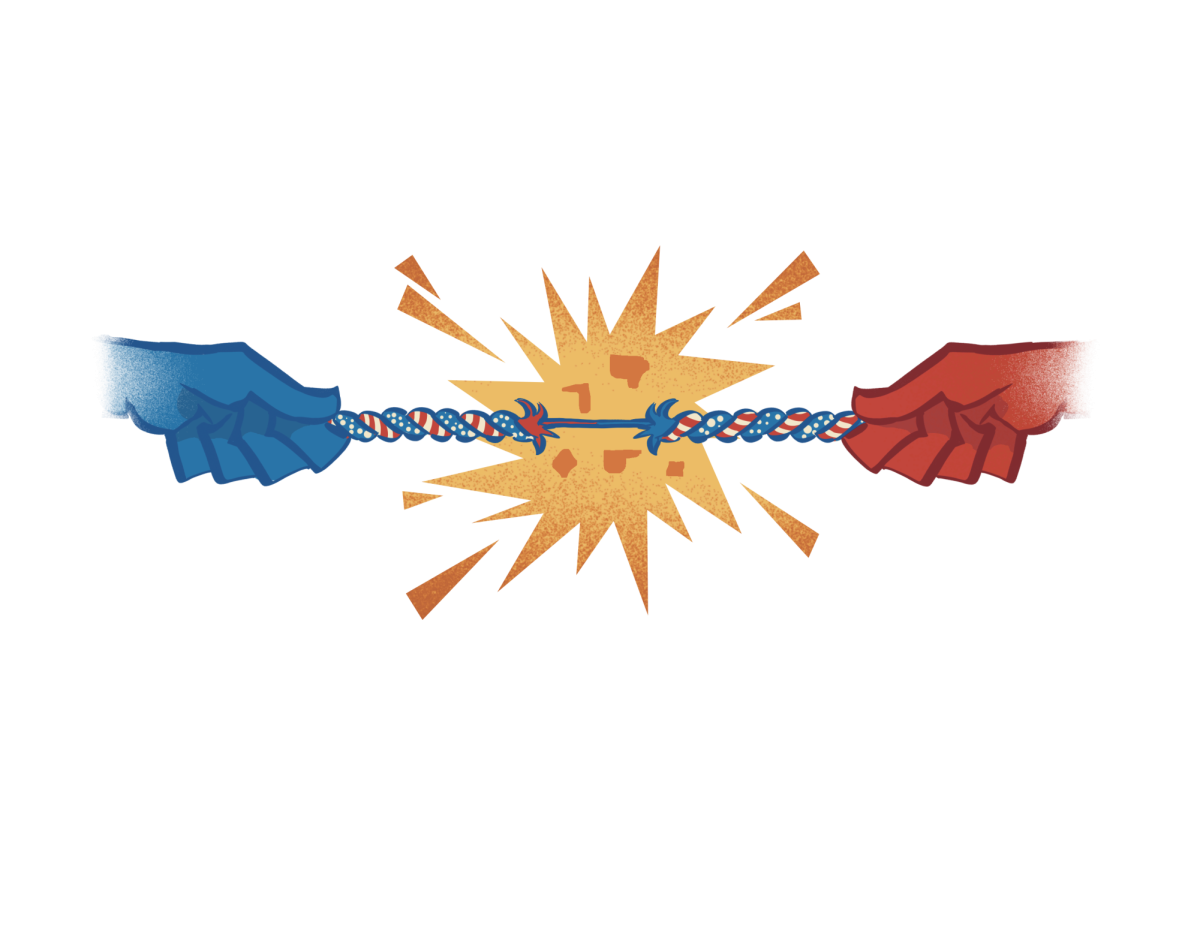

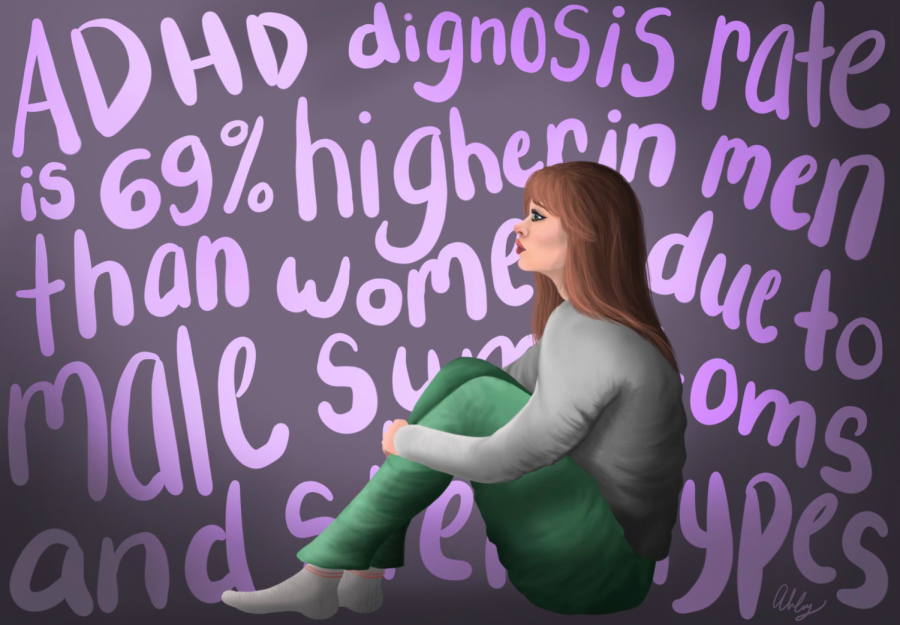

One of the problems with diagnosing ADHD at a young age is how frequently it’s reduced to young boys who have an inability to sit still in the classroom. Boys and girls statistically tend to show different symptoms — and in addition, symptoms are presented differently for each individual.

“Inattentive girls just generally tend to internalize their symptoms while boys externalize them,” Otsuka said. “Girls will go inward, meaning their anger, their struggle, their frustration — and they’re scared to tell anyone. There are all kinds of studies that have shown that when a boy and a girl present with the exact same ADHD symptoms, the boy will be referred for treatment but the girl won’t.”

Otsuka discovered she had ADHD after doctors diagnosed her son.

“Had it not been for his diagnosis, I would never have known,” she said. “Then it took a good long eight months of me studying all about ADHD for me to realize that ‘ah! well, my symptoms are different, but I have ADHD.’”

Otsuka’s discovery is not a surprise to Orlando psychiatrist Brady Bradshaw.

“The challenge is that, in general, girls are more likely to have ‘internalizing’ symptoms, and boys ‘externalizing’ symptoms,” Bradshaw said. “So boys are more likely to have behavior problems in a classroom, which is easily recognizable to a teacher and brought quickly to parents. Girls are more likely to be inattentive and so they may not be attending in class, but they are more likely to be staring out a window or daydreaming, not disrupting the classroom.”

The other problem with the frequent

behavioral differences between male and female students, especially when they’re

young children, is that they get treated differently by authority figures as a result.

“What I think happens too often is that little boys are rowdy and unfocused, and instead of correcting this behavior, many parents or teachers will just [assume] they have ADHD, which provides them a crutch and doesn’t require them to take responsibility for their actions,” Balser said. “Girls, on the other hand, are ‘supposed’ to have complete control over their actions and become disciplined from a young age.”

Bradshaw encourages young people to do some research themselves.

“I think it’s important to encourage people to get evaluated by a child psychiatrist or psychologist if they feel they may have symptoms,” she said. “A professional will be able to help differentiate and clarify the symptoms, and whether you meet criteria for ADHD. It’s always OK to get evaluated and try to learn more about yourself and how your brain works.”

I’m a first-year, sophomore staff writer. I love discussing current events and issues and my favorite treasure in the world is my cat.