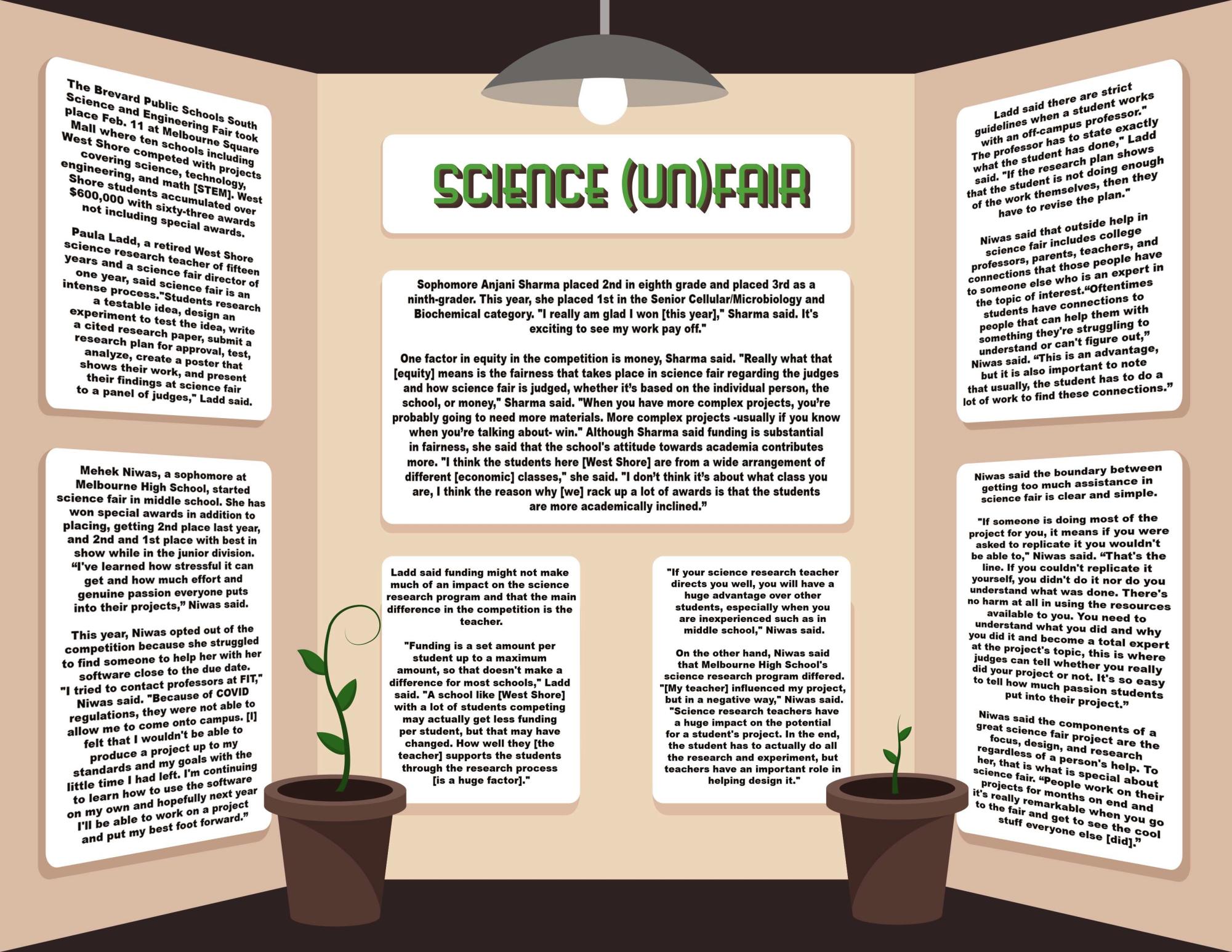

Working with a college professor and PhD students in microbiology at the University of Central Florida is not a classic high school group project. But for resourceful science research participants like sophomore Anjani Sharma, it is nothing new. The Brevard Public Schools South Science and Engineering Fair took place Feb. 11 at Melbourne Square Mall where ten schools including West Shore competed with projects covering science, technology, engineering, and math [STEM.]

West Shore students accumulated over $600,000 with sixty-three awards not including special awards.

Paula Ladd, a retired West Shore science research teacher of fifteen years and a science fair director of one year, said science fair is an intense process.

“Students research a testable idea, design an experiment to test the idea, write a cited research paper, submit research plan for approval, test, analyze, create a poster that shows their work and present their findings at science fair to a panel of judges,” Ladd said.

Sharma placed 2nd in eighth grade and placed 3rd as a ninth grader. This year, she placed 1st in the Senior Cellular/Microbiology and Biochemical category.

“I really am glad I won [this year],” Sharma said. “I believe I worked hard, and it’s exciting to see my hard work pay off. I feel like my category had really good and advanced projects. I am so excited to go to states and to meet more intellectuals.”

Mehek Niwas, a sophomore at Melbourne High School, also started science fair in middle school. She has won special awards in addition to placing, getting 2nd place last year, and 2nd and 1st place with best in show while in the junior division.

“I’ve learned how stressful it can get and how much effort and genuine passion everyone puts into their projects,” Niwas said. “It’s the type [of stress and passion] that I’ve never seen anywhere else.”

Niwas said that outside help in science fair includes college professors, parents, teachers, and connections that those people have to someone else who is an expert in the topic of interest.

“Oftentimes students have connections to people that can help them with something they’re struggling to understand or can’t figure out,” Niwas said. “This is an advantage, but it is also important to note that usually, the student has to do a lot of work to find these connections as well.”

With some students having professional guidance in the competition, another factor in equity is money, Sharma said.

“Really what that [equity] means is the fairness that takes place in science fair regarding the judges and how science fair is judged, whether it’s based on the individual person, the school, or money,” Sharma said. “A lot of the materials you need to make these experiments cost money. Getting bacteria, getting different types of solutions, they all cost money. When you have more complex projects, you’re probably going to need more materials. More complex projects -usually if you know what you’re talking about- they win.”

This year, Niwas opted out of the competition because she struggled to find someone to help her with her software close to the due date.

“I tried to contact professors at FIT,” Niwas said. “Because of COVID regulations, they were not able to allow me to come onto campus. [I] felt that I wouldn’t be able to produce a project up to my standards and my goals with the little time I had left. I’m continuing to learn how to use the software on my own and trying to find someone who [can] help guide me. Hopefully next year I’ll be able to work on a project and really put my best foot forward.”

Although Sharma said funding is substantial in fairness, she said that the school’s attitude towards academia contributes more.

“I think the students here [West Shore] are from a wide arrangement of different [economic] classes,” she said. “I don’t think it’s about what class you are, I think the reason why [we] rack up a lot of awards is because the students are more academically inclined. They have a motive to pick a higher caliber project; thus, it’s more money [awarded]. I know teachers put their own funds [towards science fair], and I’m sure there is more funding for it too. [West Shore] can really motivate and pressure the students to get deadlines and to work harder in comparison to other schools.”

Ladd said funding might not make much of an impact on the science research program and that the main difference in the competition is the teacher.

“Funding is a set amount per student up to a maximum amount, so that doesn’t make a difference for most schools,” Ladd said. “A school like [West Shore] with a lot of students competing may actually get less funding per student, but that may have changed. How well they [the teacher] supports the students through the research process [is a huge factor].”

Niwas said she thinks that because Stone Middle School’s research program was filled with resources, she had advantages over others.

“If your science research teacher directs you well, you will have a huge advantage over other students, especially when you are inexperienced such as in middle school,” Niwas said. “Some schools have better resources as well, which makes it a lot easier and reduces a lot of stress for the student. If I was at a different school, I don’t think I would have performed as well. My teacher was amazing, and he helped drive the culture at Stone [to be passionate in science fair]”

On the other hand, Niwas said that Melbourne High School’s science research program differed.

“[My teacher] influenced my project, but in a negative way,” Niwas said. “Science research teachers have a huge impact on the potential for a student’s project. In the end, the student has to actually do all the research and experiment, but teachers have an important role in helping design it.”

Sharma said that having guidance from a college professor gives her an advantage to a certain extent, but it also has its limitations.

“The professor can help make a better project with you,” Sharma said. “[However], this is still a high school science fair, and the college professor might make it [the topic] more complex for you to understand. I had that difficulty in the past. I still think if I were to understand more of the material, then I would have placed higher [in ninth grade]. The projects I choose are pretty advanced: they are college level, and they get to a point where we are working with PhD students. They do help me a lot. I think put a lot of work in, but without my college professor, I don’t know if I would be able to have as good of a project that I have now.”

Ladd said there are strict guidelines when a student works with a professor.

“The professor has to state exactly what the student has done,” Ladd said. “If the research plan shows that the student is not doing enough of the work themselves, then they have to revise the plan.”

Niwas said the boundary between getting too much assistance in science fair is clear and simple.

“If someone is doing most of the project for you, it means if you were asked to replicate it you wouldn’t be able to,” Niwas said. “That’s the line. If you couldn’t replicate it yourself, you didn’t do it nor do you understand what was done. There’s no harm at all in using the resources available to you- it’s why they are there.”

Niwas said the components of a great science fair project are the focus, design, and research regardless of a person’s help. To her, that is what is special about science fair.

“You need to understand what you did and why you did it and become a total expert at the project’s topic,” Niwas said. “This is where judges can tell whether you really did your project or not. It’s so easy to tell how much passion students put into their project. People work on their projects for months on end and it’s really remarkable when you go to the fair and get to see the cool stuff everyone else [did].”