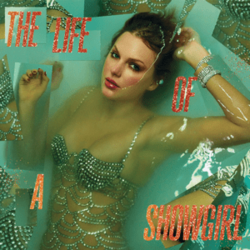

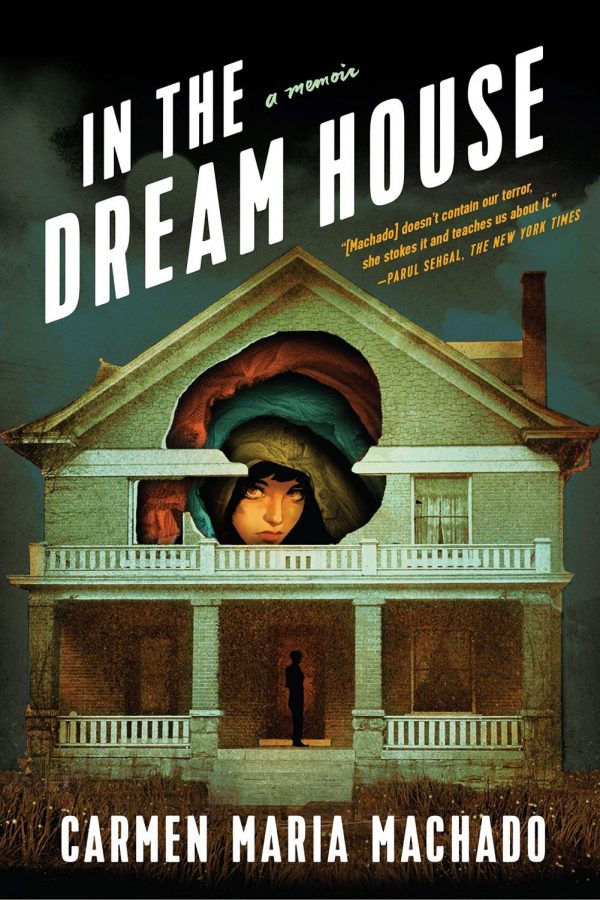

‘In the Dream House’ a gripping tale of identity, triumph

April 6, 2021

“In The Dream House” is a deeply emotional experience that grips the reader from page one and refuses to let go until long after it is finished. Published in 2019 by fiction author and essayist Carmen Maria Machado, “In The Dream House” is her first nonfiction novel, and a major departure from the whimsical and lighthearted tone taken in the majority of her previous work.

The memoir does not focus on her entire life, but rather chooses to center around a singular abusive relationship the author found herself in over the years prior to the novel’s penning. Machado does not just tell this story, however — she explains how her identity as a self-described, “fat, Cuban, and queer woman” shaped her life and identity. She also seeks to explain the untraditional and often ignored dynamic found in LGBT abusive relationships. Each of these ideas are explained and explored masterfully. Machado’s word choice, metaphor and anecdotes create a story with such poignant and universal themes that her situation becomes innately understandable, even to readers who might not have a single thing in common with her.

I read this memoir in audiobook format, and I cannot recommend this experience enough. Narrated by Machado herself, the audiobook (which is available for free on library apps such as Libby, or on Kindle) sets the novel into an entirely different context. Hearing the words come directly from the author’s mouth creates an inescapably intimate and personal experience. It also completely changes the context of certain chapters. Lines the mind might have interpreted as furious are instead mournful pleas, and the other way around. Machado reads with such passion and inflection, with such honesty and torment, with such freedom and catharsis, that the reader cannot help but to identify with and root for her. To opt to experience this book in paper format would no doubt still be a moving experience, but nothing could compare to the all-encompassing and raw emotion present in the way Machado tells her own story. And, in a novel about taking back narratives that have commonly been stolen from women exactly like Machado, in a novel that chronicles the methodical removal of Machado’s voice, hearing her read her own story feels inherently freeing.

Told through a series of anecdotes, Machado does not hold back at any point in her narrative. She tells the story of the woman she fell in love with: a 120-pound, blonde, “femme” lesbian, an ambitious writer and New York native. She contrasts this with herself: an anxiety ridden, overweight Cuban woman from a small town. She explains how their once passionate love slowly gives way to rage and torment, despite the power dynamics one may expect from a couple such as them. Machado is unbearably honest in her experience — explaining not only how her early life experiences landed her in that situation, but how anyone could land there. She writes of a deep desire to be loved, despite feeling undeserving of the affection she receives. She explains how this led her to excuse cruelty once it began, and how she was convinced to stay once the relationship turned sour. Machado also makes the bold creative decision to write the story in the second person point of view. She describes herself as “you,” which lessens the already weak separation between herself and the reader. Stories are told like a tragic choose-your-own-adventure tale, except you have no say in where the story goes. This also allows her abuser to become the singular, impersonal, “her.” Occasionally, her abuser is referred to as, “the Woman in the Dream House,” a phrase that is additionally tragic when you learn, early on, the symbolism of the Dream House. Machado begins the book by stating, “I daresay you have heard of the Dream House? It is, as you have heard, a real place.” It is a metaphor, sure, but it is also a real place — Machado and the Woman in the Dream House moved in, excitedly, early in their relationship.

Slowly but surely, the Dream House becomes a site of torment. In one particularly mournful chapter, Machado laments, “You were the sudden, inadvertent occupant of a place where bad things had happened. And then it occurs to you that one day, standing in the living room, that you are this house’s ghost. You are the one wandering from room to room with no purpose, gaping at the moving boxes that are never unpacked, never certain what you’re supposed to do. After all, you don’t need to die to leave a mark of psychic pain. If anyone is living in the Dream House now, he or she might be seeing the echo of you.” This theme continues, and the idea sticks. It sticks with the reader long after the novel has been finished.

The entire memoir does not consist of anecdotes, however. Machado also fills the in-between spaces with analysis of various works of fiction and their abusive undertones; stories such as the 1944 film “Gaslight” and how deeply impactful they are for survivors of abuse. She also uses historical cases of other lesbian abusers and how they were viewed, both in the eyes of the public and the court. At the end of the novel, Machado expresses that part of the difficulty she had in writing the memoir was the lack of comprehensive resources of lesbian abuse, or LGBT abuse in general. She states that although she understands her novel cannot serve as this source, she hopes it will be a start. This not only brings the author closer to Machado’s story, but contextualizes both it and her hopelessness. As she chronicles instance after instance of abused lesbians being refused help by the court, you begin to understand why she stayed so long.

Machado is primarily a fiction essayist, and this influence can be acutely felt in her writing. Wreathed with metaphor and fictional anecdotes, she creates a world that entirely reflects her grief. Her story is inspired, and even the titular Dream House, the location through which the story is told, is fantastical and hypnotic. Machado takes the well-established format of a memoir and twists it into something entirely her own. At no point did it feel like her story was a vanity project. It felt essential during every single page, and like a deep sigh of relief for both author and audience.

Machado’s story is one the world is richer for receiving. An exercise in empathy and understanding, in casual tragedy and loss, “In the Dream House” is an enchanting tale that should not be skipped. It is never exaggerated, and understands at every step why it was created. Machado holds the audience’s heart in a vice-grip, and refuses to let go. She holds, and twists, and squeezes and elicits emotions the reader might not have known they were even capable of feeling. Machado’s writing is an absolute must-read. To use a phrase vastly overused for less deserving works of literature, reading Carmen Maria Machado’s “In the Dream House” this soon after its publishing feels like catching a modern classic in its earliest stages.

![Sophomore Isabelle Gaudry walks through the metal detector, monitored by School Resource Officer Valerie Butler, on Aug. 13. “I think [the students have] been adjusting really well," Butler said. "We've had no issues, no snafus. Everything's been running smoothly, and we've been getting kids to class on time.”](https://westshoreroar.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/IMG_9979-1200x800.jpg)